Historical Scholarship

Key moments help us to better understand the ways that the current school system is deeply linked to state and local history. The material below was selected from the sources listed here. We recommend these authors as a starting point for further investigation:

Dr. JOHN K. CHAPMAN: Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960

Dr. J. MICHAEL MCELREATH: The Cost of Opportunity: School desegregation and changing race relations in the triangle since World War II

GRACE TATTER, M.Ed.: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools

Dr. DWANA WAUGH: From Forgotten to Remembered: The long process of school desegregation in Chapel Hill, North Carolina and Prince Edward county, Virginia

Additional Resources

Podcast: Re/Collecting Chapel Hill, by Danita Mason-Hogans, Molly Luby, Mandella Younge, Klaus Mayr

Digital History: Chapel Hill Community History, Black Women & Education by Danita Mason- Hogans, Kayla Bryant, Mandella Younge, Marissa Butler, Akanke Mason-Hogans

Oral History Archives: Southern Oral History Program

Newsletter: Stone Walls , by Mike Ogle

Timeline

— 1903 —

“All white children shall be taught in the public schools provided for the white race, and all colored children shall be taught in schools provided for the colored race, but no child with negro blood in its veins, however remote the strain, shall attend a school for the white race; and no such child shall be considered a white child. The descendants of the Croatan Indians, now living in Robeson and Richmond counties, shall have separate schools for their children..”

North Carolina Public Laws 1903, ch. 435, sec. 22; Revisal 1905, sec. 4086.

— 1909 —-

“The trustees drew the boundaries of the Chapel Hill Special Tax District to exclude all of the black neighborhoods of Chapel Hill. This was possible because of the segregated housing patterns that developed in the wake of the white supremacy movement at the turn of the century. However, the trustees’ aim was not to set up a dual Jim Crow system of public education in Chapel Hill, but rather to establish a system of white public education, with no provision for black children. The UNC community would provide no tax support for the education of the children of the menial laborers who staffed the university, maintained the streets of the town, laundered clothing, cooked meals, and raised the children of professors.”

From Chapman, p.120

— 1913 —

“… discontent with the county system had become so intense that Rev. Hackney and others called a mass meeting at which the black community decided to establish a private school. This school was named the Hackney Training School [later renamed the Orange County Training School (OCTS)*] and was located on Merritt Mill Road. It enrolled approximately two hundred students and employed two academic teachers and two music teachers, as well as Rev. Hackney.”

From Chapman, p.121

*OCTS is later renamed Lincoln High School.

— 1929 —

Chapel Hill schools separate from Orange county to gain more local control. City leaders are able to direct local tax dollars solely to Chapel Hill students. Local leaders discontinue funding an eight month school year for the Orange County Training School. Instead, Black schools are only supported for the six month minimum required by state law.

— 1930 —

Blacks in Chapel Hill vote to assign themselves an extra tax to cover the costs of keeping the OCTS open for the full eight month school year.

From Waugh, p.44

— 1954 —

Brown v. Board of Education is decided

— 1955 —

“The people of North Carolina know the value of the public school. They also know the value of a social structure in which two distinct races can live together as separate groups, each proud of its own contribution to that society and recognizing its dependence on the other group. They are determined, if possible, to educate all the children of the State. They are also determined to maintain their society as it now exists with separate and distinct racial groups in the North Carolina community.” From the North Carolina General Assembly Manifest

From Waugh, p. 69

“Like I said, ever since probably about five years old I’d just dream and dream and dream about going to Lincoln because Lincoln was just like electricity. The school was so vibrant and had so much, it’s just kind of hard to explain it, but it was so alive. And it used to just beat like a drum. And it connected with everybody in the community.”

Keith Edwards, January 2, 2001 interview Southern Oral History Program

From Waugh, p.158

“As former student Edwin Caldwell recalled, black teachers “gave us a philosophy of life, and they taught us ethics. I felt they taught me to be a critical thinker. And I know that they taught me to believe in myself. [They] instilled a pride in us that made us believe there was nothing we could not do.”

Edwin Caldwell, December 5th, 2000, interview Southern Oral History Program

— 1955 to 1965 —

“North Carolina school districts denied transfer requests for a variety of reasons. In Chapel Hill, one black student’s request was denied because he wanted to attend a white school, which defied the Supreme Court’s alleged color-blind application of student assignments. From 1956 to 1963, approximately twenty-four black parents petitioned to transfer their elementary or secondary child to an all-white school.”

Waugh, p. 105, footnote

“Often Chapel Hill school board officials denied the transfer requests of black junior high or high school black students. School board records bear out the consistent rejection of older, school-aged black transfer petitions. For example, Charles Lee Bynum, Sheila Pearl Bynum, Ted Stone, and Percy Tuck Jr. all applied for reassignment and were denied.”

Waugh p. 107, footnote

— 1960 —

“The choice is not between segregation and integration; it is between some integration and total integration.... [If we resist all integration], it is a foregone conclusion that the winner will be total integration, or that the schools will be closed.... Token integration..,will save the state and save the schools.... This is moderation.” North Carolina State Judge Braxton Craven

From Waugh, p. 69

— 1965 to 1966 —

“The percentage of African American teachers fell precipitously in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro school district around the time that schools there desegregated...”

From McElreath, p. 463

— 1967 to 1968 —

“..the school board approved forty-one administrators, teachers, guidance counselors, and coaches to work at Chapel Hill High. Only seven African Americans composed the staff. In 1964, Lincoln High had eighteen blacks on staff, including one black principal and two black guidance counselors. A majority of these educators lost their positions and had to seek work outside of Chapel Hill with the implementation of desegregation. Of the African Americans who kept employment with the school system, many were demoted.”

From Waugh, p. 156

— 1970 —

The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare turns its attention to intra-scholastic segregation.

— 1972 —

The Federal Emergency School Aid Act of 1972 (ESAA) aims to eliminate minority group segregation and discrimination within schools.

“..school authorities had to either eliminate or justify ‘any procedure for the assignment of children to or within classes which results in the separation of minority group from non-minority group children for a substantial portion of the day…Congress provides an exception for ‘bona fide ability grouping…as a standard pedagogical practice…”

From McElreath, p. 418.

— 1973 to 1974 —

“Chapel Hil had [difficulty] convincing HEW that it had eliminated discriminatory practices in its classroom assignments…HEW first raised concerns about racially identifiable classes at Chapel Hill High School in [1973]. HEW noted that black students were heavily over-represented in the district’s special ed programs. The federal regulators sent investigators to examine the district’s records and procedures. In 1974, HEW continued to question the Chapel Hill’s EMR [“Educable Mentally Retarded”] program and also began to challenge the justification for racially identifiable classes in the system’s two junior high schools.”

From McElreath, p. 424

— 1977 —

North Carolina begins minimal standards testing

— 1983 —

National Commission on Excellence in Education issues its report: A Nation at Risk.

The report argued that “the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people.”

— 1984 —

The year after A Nation at Risk was published, the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Board of Education began focusing on gifted education.[1]By 1990, administrators in Chapel Hill had commissioned three committees and reports on the topic.

From Tatter, p. 37

— 1991 —

December 1991 - Proposal for the Achievement of Gifted Minority Students is presented to the Board of Education.

“Ms. House reminded the Board it had received a revised plan for the academically gifted program…[that] had recommended that the district look separately at service delivery to gifted minority students and bring recommendations back to the Board on how to serve this population.”

From Board of Education minutes, Dec 16th, 1991

Image Sources

1903 - North Carolina Public Laws 1903, ch. 435, sec. 22; Revisal 1905, sec. 4086

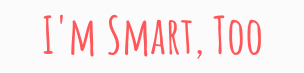

1909 - Chapel Hill, December, 1915, see additional maps in Chapman’s appendix

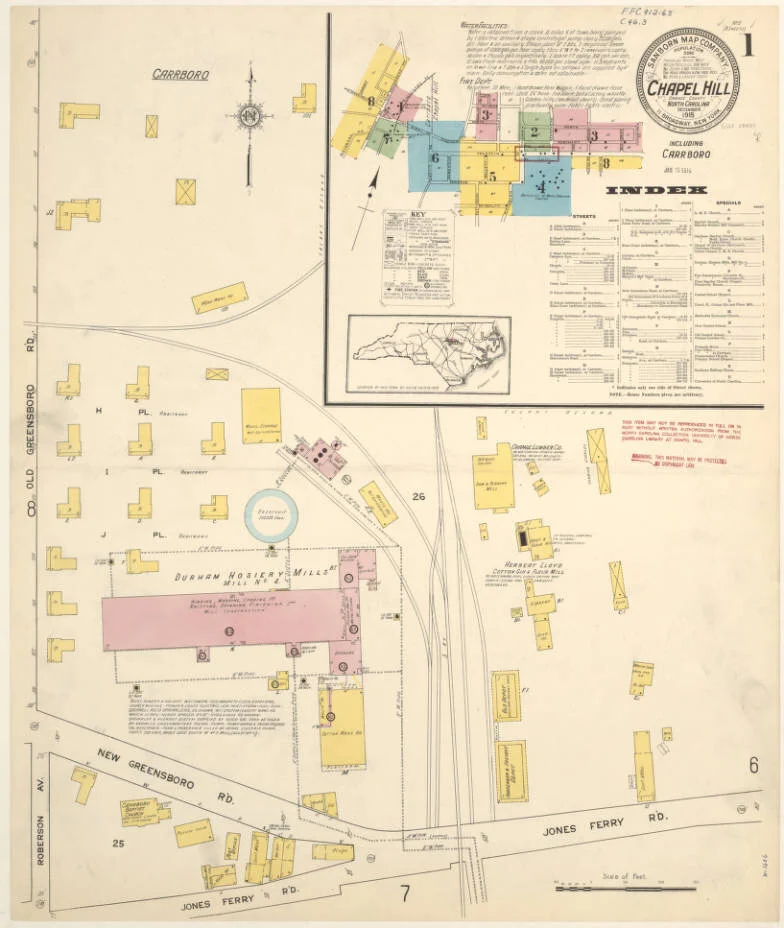

1913 - Rev. L.H. Hackney, courtesy of rootsweb

1929 - Orange County Training School, Copyright UVA Library

1955 - Excerpt from the 1955 North Carolina General Assembly

1955 - Lincoln High School, 1953, Copyright Roland Giduz Photographic Collection, curtesy Wilson Library, UNC

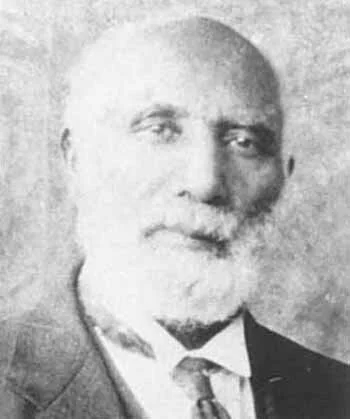

1955 - Chapel Hill Weekly, July 5th, 1957 Copyright The News & Observer

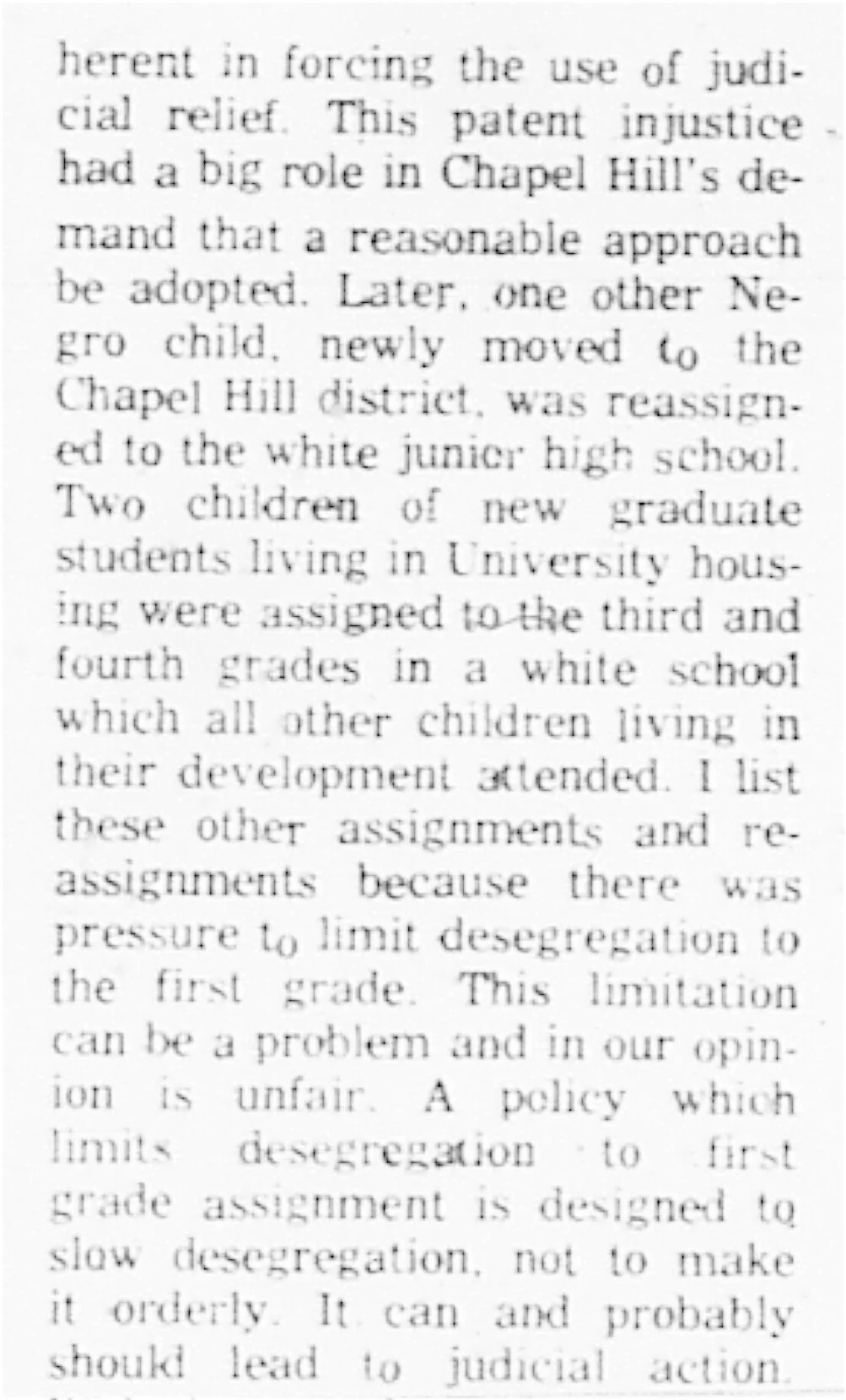

1955-1960 - Chapel Hill Weekly, May 3rd, 1962 Copyright The News & Observer

1965-1968 - McElreath, p. 463, footnote 28

1972 - Copyright Mason-Hogans family

1991 - CHCCS school board minutes archive

Oral History Sources

1950s:

a) Keith Edwards, interview by Bob Gilgor, January 2, 2001, K-0542, in the Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007), in the Southern Historical Collection, in Wilson Library, at the University of North Carolina

b) Edwin Caldwell, Jr., interview by Bob Gilgor, December 5, 2000, K-532, Supplemental Materials to Interviews, December 5, 2000 in the Southern Oral History Program, (#4007) in the Southern Historical Collection in Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina, 2.